Climate change, nuclear war occupy Jerry Brown in retirement

Climate change, nuclear war occupy Jerry Brown in retirement

WILLIAMS, Calif. (AP) — Former California Gov. Jerry Brown is living off the grid in retirement, but he’s still deeply connected on two issues that captivated him while in office and now are center stage globally: climate change and the threat of nuclear war.

The 83-year-old Brown, who left office in 2019, serves as executive chairman of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, which sets the Doomsday Clock measuring how close humanity is to self-destruction. He’s also on the board of the Nuclear Threat Initiative.

In an interview with The Associated Press, Brown commended President Joe Biden for not raising the U.S. nuclear threat level after Russian President Vladimir Putin made veiled threats to use his country’s nuclear arsenal amid its war in Ukraine. Brown also urged Biden to resist Republican calls to increase oil production as gasoline prices soar.

“It’s true that the Russians are earning money from oil and gas, but to compound that problem by accelerating oil and gas in America would go against the climate goals, and climate is like war: If we don’t handle it, people are going to die and they’re going to be suffering. Not immediately, but over time,” said Brown, a Democrat.

Brown spoke to the AP last week from his home in rural Colusa County, about 60 miles (97 kilometers) northwest of Sacramento. The land in California’s inner coastal mountain range has been in Brown’s family since the 1860s, when his great-grandfather emigrated from Germany and built a stagecoach stop known as the Mountain House.

The home Brown and his wife, Anne Gust Brown, finished building in 2019 is called Mountain House III. The home is powered entirely by solar panels and is not connected to any local utility.

Though Brown is retired from electoral politics after serving a record four terms as California’s governor — from 1975 to 1983 and 2011 to 2019 — he is hardly absent from public life.

Brown has organized conversations with John Kerry, Biden’s special presidential envoy for climate; Xie Zhenhua, China’s climate envoy; and former U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon. He created and chairs the California-China Climate Institute at the University of California, Berkeley, which aims to boost collaboration on climate-related research and technology.

“No matter how antagonistic things get, cooperation is still the imperative to deal with climate and nuclear proliferation,” he said.

At the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, he brings an important political perspective as its scientists consider how to get their message out, said Rachel Bronson, the group’s president. Last week, he joined the organization’s science and security board as they formulated a statement on Putin’s nuclear threats.

The scientists decided to not update the Doomsday Clock, which in 2020 was moved ahead 20 seconds to be set at 100 seconds to midnight, the metaphorical time representing global catastrophe. They did, however, warn Russia’s invasion has brought to life the “nightmare scenario” that nuclear weapons could be used to escalate a “conventional conflict.”

Bronson pursued Brown for a leadership role as his governorship ended because of the deep interest he’d shown on its nuclear work and his capacity to understand big threats.

“He thinks about existential risk,” Bronson said.

Indeed, Brown is a deep thinker on any number of issues, from hummingbirds to the very meaning of life and death. He trained to be a Jesuit priest but eventually abandoned those ambitions to follow his father into politics. Edmund “Pat” Brown was California governor from 1959-1967.

Jerry Brown brings a philosophical approach to life and work, often ready with a Latin phrase or motto to summarize his views. He has long lamented that the buildup of nuclear weapons and climate change fail to capture enough attention in the face of more immediate concerns — these days the coronavirus and inflation.

“We have to have enough bandwidth to look at the big issues, because if they get away from us we won’t have the little issues to worry about,” Brown said.

He warned a Republican takeover of the U.S. House after this fall’s midterms, coupled with the possibility of the Supreme Court limiting the federal government’s power to regulate greenhouse gas emissions, would make a climate “catastrophe all the more likely.”

Though Brown has long contemplated the fate of the planet, he’s perhaps more connected to it than ever before. He gets his power from the sun and water from a well. Fueled by climate change, California’s wildfires have become hotter, more unpredictable and more destructive in recent years and the location of Brown’s 2,500-acre (1,012-hectare) ranch has him living closer to the threat than ever.

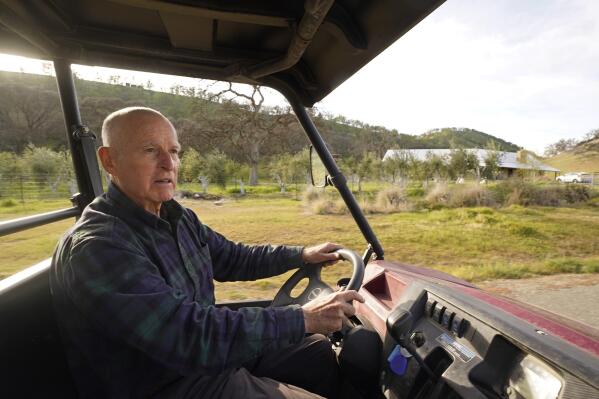

He hasn’t gone entirely green — he zips around his property on a gas-powered ATV. He’s studying the trees and flowers, determined to learn their names, and in the fall he hosts friends to help harvest olives, which he has pressed into oil.

He’s offered his property as a meeting space for the California Native Plant Society, entomologists, and forestry and fire experts. Last fall the forest experts put together a declaration calling for the state to focus on better forest management to decrease the severity of wildfires. Many of their suggestions mirrored those being pursued by Gov. Gavin Newsom’s administration.

The entomologists, meanwhile, spent two days on the ranch for a planning retreat about how to protect California’s insects. Brown allowed them to survey his land and two researchers found new species — an ant and a beetle, said Dan Gluesenkamp, executive director of the California Institute for Biodiversity and organizer of the retreat.

Brown joined the scientists for meals to grill them on their research.

He “clearly reveled in sitting around the picnic table for dinner and having super hardcore conversations with the smartest entomologists on the planet,” Gluesenkamp said.

Sitting outside his home, Brown said he recently pondered what might have been had he won one of his three presidential campaigns, the last in 1992. He decided he’d much rather be in Colusa County.

“I’m very happy where I am — it’s a very amazing place. I can’t imagine being in a better place,” he said.

He then wondered aloud whether he could have avoided the same mistakes as those who became president.

Then he quickly switched to considering why a hummingbird that caught his eye was moving so quickly from tree to tree.