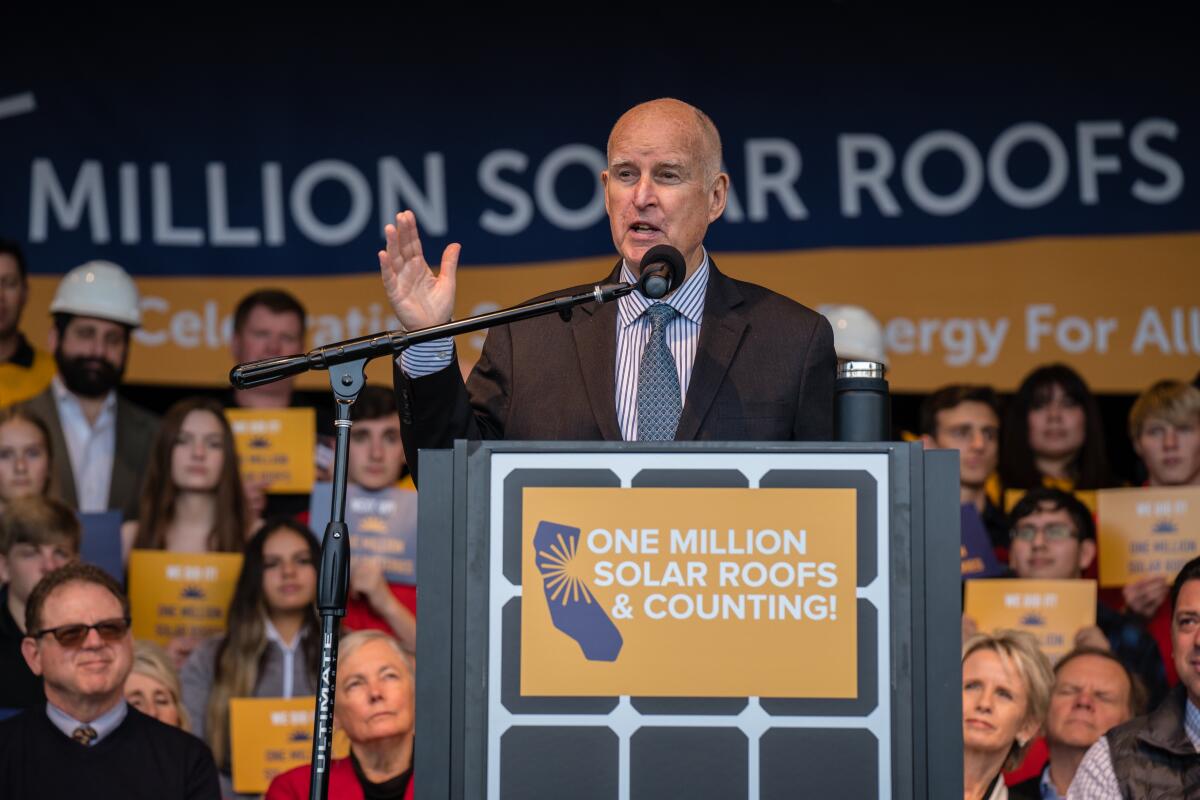

Jerry Brown was surprised — and thrilled — by Joe Manchin’s climate deal

This is the Aug. 4, 2022, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

When news broke last week that U.S. Sen. Joe Manchin III had at long last agreed to support a sweeping climate bill — and that it would include $369 billion to support clean energy and environmental justice initiatives but would also require continued oil and gas leasing on public lands and waters — I found myself wondering: What would Jerry Brown think?

Brown is considered a global leader in the climate fight. As California governor, he signed a 100% clean energy law and served as an unofficial climate ambassador abroad. He faced criticism for doing little to limit Golden State oil production, but he was still miles ahead of most high-profile politicians. He’s continued working on climate since leaving office in 2019, chairing the California-China Climate Institute and serving as executive chair of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

So I was curious what Brown had to say about the politics of the Manchin deal, and the tradeoffs made to win over the coal-loving West Virginia Democrat — including a deal to speed up the approval process for fossil fuel pipelines and natural gas export plants. Most climate advocates think it’s a worthwhile package overall, but what about Brown?

Brown agreed to speak with me from his Colusa County ranch, where he said it was 102 degrees outside. Fortunately, the climate-friendly electric heat pump he’d installed at his off-the-grid, solar-powered home was keeping him cool.

“It heats and cools. So far it’s been very good,” he told me.

Here are some highlights from our conversation, edited and condensed for clarity.

ME: How did you react when you saw that Manchin had finally reached a deal with Democratic leadership on what’s now being called the Inflation Reduction Act, after a year of negotiations?

BROWN: I was surprised. I was not informed of the internal machinations of the Senate chamber. So things may have been going on all the time. That’s probably why President Biden kept pushing, because there were indications that Manchin would eventually vote for something. As I’ve learned, the legislative process — you don’t always know what people want. Very often, the legislators don’t know what they want.

And this is all very new. During the Trump time, when there was Republican control, they didn’t want to do anything on climate. There’s still a massive idiosyncratic climate denial by Republicans in the American Senate. So it has just been the Democrats working on this thing, and they haven’t really had a lot of habit. As a Congress, they should have been working on this stuff since they first heard about it from James Hansen back in the ’80s.

ME: The $369 billion for clean energy and climate in the bill — that’s less than the $555 billion in Biden’s earlier Build Back Better legislation, and much less than the $2 trillion he campaigned on. Do you think it’s enough to confront the enormous climate challenges we’re facing?

BROWN: It’s a huge bill. That’s a lot of money. People are saying it’s the most significant move on climate ever.

Now is it bigger than Build Back Better? Well, that was an idea, that was a proposal — that was the president’s imagination. Now we’re dealing with something that is getting close to being real. That’s the way the process works. You have to go from idea to realization, and there’s a lot of modification along the way.

So I would say this is very impressive, and it’s a good sign that Manchin decided to go along. Because it means that he appreciates what’s being done, and he wants to be part of it. That’s a validation of concept for climate action. It’s getting traction.

ME: The compromises that were made to win Manchin’s vote — what do you make of those tradeoffs?

BROWN: Like sausage, you don’t want to look too closely at how it’s made. When I got the gas tax bill in California, to get the one Republican vote that I got in the state Senate — that senator got $500 million in transportation programs for his district. That is the nature of the legislative process.

ME: There are activists who say the tradeoffs in the climate bill will lock in long-term emissions we can’t afford.

BROWN: We’re locking in emissions right now. We have coal plants, gas plants. How many vehicles do we have on the road, and how long are they going to last? If you want to get serious, you could say, “OK, in two years we’ll take away all the gas cars, we’ll buy them from you. And you’ll get an electric car in return.” That’s not feasible. We’re still a fossil fuel civilization.

Now, we’re moving away. In California, we get half of our electrical generation from renewables, if you count nuclear and hydro. But if you want to win victories, you’re going to have some more oil leases. We are drilling new oil wells every day. If you want to reduce the oil produced, you must reduce the oil consumed. It’s just that simple. If you don’t reduce consumption, and you reduce production in America, they’ll just get that oil from somewhere else.

So the goal is to reduce consumption. This bill does that, and it does that with all these different investments. So it’s not perfect, but we don’t live in a perfect world. There are 50 Republicans in the Senate, and they don’t want to do any of this.

ME: Would you say America can truly serve as a world leader on climate now, assuming this bill passes? Or will it still be up to California to set an example and push other countries to do better?

BROWN: This is good what we’re doing — but no, it’s not enough. Even California is not doing enough. The country and state are doing all they can politically, and they’ll do more. But the resistance is huge. You can get $40 billion for Ukraine from Congress. It’s pretty hard to get $40 billion to change out the automobile fleet from fossil fuel to renewable.

You have to have a clear view here. This is Mitch McConnell’s Congress as much as it is Chuck Schumer’s.

ME: If you were in White House, what would you do next on climate, after signing this bill?

BROWN: I’ve been trying my darnedest to get a closer partnership with China. China is 27% of global emissions, America is 13%. So China and the U.S. must be the leaders. That is the most important form of leadership, a joint effort by China and the U.S. to move as rapidly as possible to a zero-emission economy. It’s going to take decades, but we’ve got to get going.

ME: You mentioned even California is not doing enough. What do you think about the state’s continued support for fossil fuels on the power grid, to keep the lights on when solar panels and wind turbines aren’t generating?

BROWN: If you want to get more gas-fired plants, the best thing to do is to shut them all down now. And then when the massive blackouts come, the politics will be so powerful that you’ll get even more gas plants than if you make sure that the lights don’t go out in the meantime.

If you push too far, there’s a backlash. When my father was governor, he had a water plan, a master plan of education, civil rights. And then Reagan comes in, wins by a million votes. Then I’m in office eight years, and I appoint some pretty liberal judges. Then Deukmejian comes along, and then Pete Wilson comes in. He appoints very conservative judges, builds 20 new prisons.

So if you maybe try to move slower, you end up moving faster. What is that about the tortoise and the hare? The idea is to achieve the goal. And what is the fastest way to do that? Doing it in a manner that continues uninterrupted. And to do that, you have to avoid backlash.

ME: Are there any provisions in the Senate climate bill that you particularly like?

BROWN: Supporting domestic production of battery technology, of solar panels. What did the Chinese do? They brought the cost down. They went from very little to 80% of the world’s solar manufacturing, and they did it with government investment. So they’ve shown the way. A close collaboration between public investment and private business can achieve a lot. And I think building up our own domestic industry will make it more popular, will build a constituency that will then promote it even more.

Getting more gas cars off the road is also good. The provisions are a myriad, and they all fit into a piece. It’s not one thing. Emissions are coming from gas wells and belching cows, and we’re burning up oil. Plastics. You’ve got ships, you’ve got planes, you’ve got trains, you’ve got houses. There are so many different sources of this that we must bring down much faster.

ME: You mentioned you’ve got an electric heat pump. I assume you’re pleased to see money in the Senate bill to support that technology, especially as Los Angeles and other major cities discourage gas heating and cooking.

BROWN: You’ve got to have electric heating, and you’ve got to have electricity generated by renewable energy, or storage. There’s so much to do that in the short term, you’ve got to throw a lot of money out. Of course you want to do it wisely.

We have a lot of other sidebar activities that seem very important — but they’re not as important as climate change. It’s the No. 1 existential threat to the world, and even if we accelerate our moves, there’s going to be massive migration. There’s going to be political instability. The biggest human rights issue, bar none, is a billion people in India and other parts of the world that are going to suffer because they don’t have nice air conditioning like most Americans have. They’re going to suffer greatly.

ME: There’s $30 billion in the Senate bill to help existing nuclear plants stay open. You’ve done a lot of antinuclear work in your career, including fighting the Diablo Canyon plant in California. What do you think of the push by many climate advocates to support nuclear reactors, since they can produce zero-emission electricity around the clock?

BROWN: I think even Gavin Newsom wants to keep Diablo Canyon open. It is a fair argument. Certainly keeping some nuclear plants open, that’s an easier question than building new ones, because the current technology takes an awful long time, it’s very expensive. Certainly investing in a safer, more standardized, more modular nuclear is a good idea.

With existing plants, you have to look at each case, look at the merits. See what your alternatives are. For example, Germany closing down nuclear and buying coal — no, I don’t agree with that. They should have kept them open for a while.

ME: If you were still in office, would you try to rescue Diablo Canyon, like Gov. Newsom is attempting?

BROWN: I’m not going to weigh in on that one. There are a lot of people who have their views. I know some people who think it should not stay open. Other friends of mine, equally intelligent, say, “No, keep it open for a while.”

On that note, here’s what’s happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

“What we’re seeing in the western United States and in British Columbia in the last few years, I would not have expected to see until 2040.” That’s what one scientist told my colleague Corinne Purtill about the McKinney fire, which in less than a week has exploded into California’s largest blaze this year and spewed a “fire-breathing dragon” of soot and ash into the stratosphere. At least four people have died as the fire tears through Klamath National Forest, threatening towns such as Yreka, destroying more than 100 homes and other structures and requiring the rescue of at least 60 hikers on the Pacific Crest Trail. If Native Americans had been allowed to keep setting low-intensity fires — and there hadn’t been commercial logging — the blaze likely wouldn’t be so bad, The Times’ Alex Wigglesworth and Hayley Smith report. And it isn’t the state’s only active conflagration: The Oak fire near Yosemite National Park has also prompted evacuations. Why did that blaze get so much worse than the nearby Washburn fire, which started within Yosemite? A half-century of controlled burns and managed fire at the park likely played a role, Alex writes.

As you may have noticed if you live in Southern California, it’s not only hot this week — it’s humid. My colleague Nathan Solis wrote about the miserable, muggy weather, and yes, there’s a climate connection: Much of the country is experiencing an increase in humid heat as the planet warms, according to nonprofit research group Climate Central. Portland, meanwhile, just saw seven straight days of temperatures above 95 degrees, and Seattle six straight days above 90 — records for both cities, per the Associated Press. Here in L.A., the Midnight Mission — which serves the homeless population — says it’s seeing more heat-related illnesses on skid row as the planet heats up. The organization badly needs water donations, The Times’ Rebecca Schneid reports.

A top climate and conservation official at California’s State Water Resources Control Board just resigned — and he’s got some searing criticisms of Gov. Gavin Newsom. Max Gomberg told my colleague Ian James the Newsom administration hasn’t done nearly enough to equitably confront climate and water challenges, letting farmers keep using far too much water and not doing enough to assist low-income families struggling with high water bills. A spokesperson for the governor responded that Newsom “is doing more than any other state to adapt to our changing climate” — which, if you ask me, could still be true without necessarily invalidating Gomberg’s criticisms. Anyway, Newsom is definitely putting a bunch of political capital into one particular water project: a controversial replumbing of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta. Details here from The Times’ Susanne Rust.

WATER IN THE WEST

Arizona golf courses use way more water than they’re supposed to — and state officials largely let them get away with it. That’s the key finding of this fabulous investigation by Balint Fabok for the Arizona Republic. The dry-and-getting-drier Grand Canyon State has more than 200 golf courses. The industry likes to say that it generates $4.6 billion in economic activity, but the story points out that’s just 1.2% of Arizona’s economy — for an industry that uses 2% of its water. Meanwhile, in California’s Coachella Valley — which has 120 golf courses all on its own — one Palm Springs course will soon become a nature preserve, with a botanic garden, walking trails and floating docks for migratory birds. Here’s the story from the Desert Sun’s Erin Rode.

Californians cities reduced water use 7.6% in June, compared to 2020 — but there are disparities across the state. In Southern California, savings were just 5.9%, compared to 12.6% in the Bay Area, per my colleague Salvador Hernandez. That’s progress over previous months, but still a far cry from the 15% cutback Gov. Gavin Newsom called for last year. Water supplies are especially tight in Burbank, which will ban outdoor water entirely for two weeks during repairs to a leaky Colorado River pipeline, Melissa Hernandez reports. For cities where outdoor irrigation is restricted but not banned, you can still water your lawn if it’s not your watering day; just go to the L.A. Zoo to pick up recycled water from the city, The Times’ Summer Lin writes. (You’ll have to fill out an application and take a training class first.) Los Angeles does have big plans to bolster supplies by storing more water in underground aquifers — but decades of aerospace and industrial pollution pose an obstacle, columnist Steve Lopez writes.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

The Biden administration will halt new oil and gas lease sales in Central California — at least temporarily. Details here from my colleague Tony Briscoe, who writes that the leasing pause follows the Trump administration’s efforts to allow drilling and fracking across more than 1 million acres of federal land. Further south, Amplify Energy agreed to reimburse Orange County nearly $1 million for the costs of responding to last fall’s offshore oil spill, The Times’ Melissa Hernandez writes. Despite those developments, the oil industry and its workers remain a political powerhouse in the Golden State. The Western States Petroleum Assn. spent nearly $2.5 million lobbying the Legislature and state agencies during the second quarter of this year. The trade group is also airing television ads in Florida attacking Newsom’s climate and clean energy policies, as CalMatters’ Emily Hoeven notes.

Disney refused to air Democratic Party ads on its Hulu streaming service about Republican efforts to block climate action, abortion rights and gun control — before reversing course and changing its policy on political ads. Here’s the initial story from the Washington Post’s Michael Scherer, as well as more context from my colleagues Seema Mehta and Ryan Faughnder on the political controversies Disney’s been embroiled in lately. (Also, here’s Ryan’s update on the company’s change of policy after a public backlash.) Even before Disney acquired Pixar, Marvel, Lucasfilm and 21st Century Fox, the company was the world’s most influential storyteller — so its decisions about how and where to bring climate into the conversation, if at all, matter immensely.

Vice President Kamala Harris announced more than $1 billion in federal spending to help states respond to climate-fueled disasters such as extreme heat, wildfires and flooding. The Associated Press’ Matthew Daly has the details. In Congress, meanwhile, a bill from Democratic Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden would create the first-ever national strategy for protecting America’s grasslands — a key carbon sink, and one increasingly threatened by rising temperatures, the Washington Post’s Maxine Joselow and Vanessa Montalbano write. Both of those initiatives could be especially valuable in Colorado, where Gov. Jared Polis has a reputation as a national leader on climate — even as many activists say he’s not doing enough, per Elisabeth Kwak-Hefferan at 5280 magazine.

THE ENERGY TRANSITION

A renewable energy developer has agreed to pause construction of a Nevada geothermal plant while federal officials study whether it would harm the endangered Dixie Valley toad. It’s only the latest example of clean energy and conservation coming into conflict, the Associated Press’ Scott Sonner writes. In better news for geothermal, the Biden administration is making a $165-million investment to use oil and gas technology to help grow the clean-energy technology, Reuters’ Liz Hampton reports.

The federal government is poised to approve a nuclear waste storage facility on cattle grazing land in New Mexico. But will it ever actually get built? And when would spent fuel from Southern California’s shuttered San Onofre nuclear plant get there? The San Diego Union-Tribune’s Rob Nikolewski tackled those questions. (Spoiler alert: There are plenty of hurdles yet to be cleared.) In other nuclear news, federal regulators are poised to approve the reactor design for the nation’s first small modular nuclear plant, Utility Dive’s Larry Pearl writes. The current plan is for the facility to be brought online at Idaho National Laboratory in 2029.

New research suggests electric heat pumps — a possible replacement for gas furnaces and boilers — perform well in below-freezing temperatures. The research was conducted in Maine, but it’s got national implications, since the ability to keep people warm in super-cold weather has been one of the biggest concerns about heat pumps, as Sarah Shemkus writes for Energy News Network. In related news, the oil and gas industry is spending loads of money to try to oust a Washington state lawmaker who has been pushing to replace gas heating and cooking with electric appliances, HuffPost’s Alexander C. Kaufman reports. And speaking of heat pumps, U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm gave them a shout out on “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert” this week. Granholm also discussed the Manchin climate deal, high oil prices and federal funding for electric vehicle chargers.

OIL AND GAS POLLUTION

California doesn’t count methane leaks from abandoned oil and gas wells in its greenhouse gas inventory. That’s a problem, because methane is a powerful planet-warming pollutant — but the state is beginning efforts to estimate those emissions, the Associated Press’ Drew Costley reports. The AP’s Michael Biesecker and Helen Wieffering also have an important investigation that uses infrared camera data to identify 533 methane “super emitters” in the Permian Basin, a sprawling oil- and gas-producing region across parts of Texas and New Mexico. Texas is basically ignoring the problem, while New Mexico is trying to crack down.

There are all sorts of barriers to low-income Californians who want to stop burning oil and switch to an electric car. There are several financial incentive programs, but they’re typically easier for wealthier applicants to navigate, and they can run out of money fast, per this excellent story by Nadia Lopez for CalMatters. High gas prices, meanwhile, are hitting Golden State residents hard, especially Black and Latino families, according to a new poll — but two-thirds of Californians still oppose new offshore oil drilling, my colleague Phil Willon writes. In addition to helping drivers spend less on fuel, electric cars can have benefits for the power grid. America’s first “vehicle to grid” project is now online in San Diego, where electric school buses will send power into the grid and help keep the lights on when they’re not shuttling students, the San Diego Union-Tribune’s Rob Nikolewski reports.

WESTERN WILDLIFE

Warming ocean waters from climate change mean more great white sharks in Monterey Bay. That’s the conclusion of new research from the Monterey Bay Aquarium, which tracked 79 juvenile sharks using electronic tags and found that the predator “has not only adapted to the perils of a warming planet but thrived in them,” my colleague Melissa Hernandez writes. At another aquatic wonder, Lake Tahoe, plankton populations are plummeting — and that could help improve the water’s clarity, at least for the next few years, per the latest “State of the Lake” report from UC Davis. Here’s the story from The Times’ Noah Goldberg.

One of the largest Audubon Society chapters, Seattle Audubon, is changing its name. Namesake naturalist John James Audubon was “an enslaver and a strong critic of those who sought to free African Americans from bondage,” the Washington Post’s Darryl Fears writes, and that prompted the chapter’s board to vote 9-0 for a change. New name TBD. It’s yet to be seen if the move will inspire any other Audubon chapters — there are more than 450 — or the National Audubon Society to follow suit.

Was Yellowstone’s deadliest wolf hunt in 100 years an inside job? So asks the Intercept’s Ryan Devereaux, in a fascinating investigation tracing the history of wolf extermination and reintroduction in the Northern Rockies — and the right-wing backlash that’s led to an explosion in killings under Montana Gov. Greg Gianforte (who actually killed a Yellowstone wolf just outside the park himself — a few years after he violently assaulted a journalist). In other hunting news, I did not realize soccer cleats made from kangaroo leather are so popular. Animal welfare advocates say California has failed to adequately enforce its 50-year-old ban on the sale of kangaroo parts — so they’re suing a company they say is getting away with it, The Times’ Louis Sahagún reports.

ONE MORE THING

It’s been 3½ months since Rick Caruso — one of two remaining candidates for Los Angeles mayor — told me through a campaign spokesperson that he’d release a “comprehensive climate plan...in the coming weeks.” He still hasn’t done it.

At a news conference this week, my L.A. Times colleague Julia Wick asked the billionaire real estate developer what’s going on. Caruso told her his campaign would be releasing the climate plan “shortly,” and that it would be “very aggressive.”

“It’s based off of best practices that we’ve seen happening around the world. It’s based off, frankly, the personal experience that I’ve had in running my company and building my projects,” he said. “It’s based off what we’ve done down at USC, and the leadership role on sustainability there. It’s also based on what L.A. has adopted and where I think we can do a better job.”

We’ll see what happens. It’s three months until Election Day, when Caruso will face off against U.S. Rep. Karen Bass.

OK, ONE OTHER THING

I’m still making my way through a first-time viewing of “The West Wing,” and I was fascinated to watch the Season 6 episode “Drought Conditions” this week. There’s a whole storyline about Western water politics, and it includes White House press secretary C.J. Cregg — played by the great Allison Janney — making the following comment about the Colorado River:

“It’s not a drought. It would be a drought if we were experiencing far less than average annual rainfall, but we’re not. We’re dealing with 58 million people wrestling over one river’s water, based on calculations taken in what we now know were 20 flood years.”

The episode aired in 2005 — 17 years ago! But Cregg’s comments couldn’t be more relevant today.

Yes, we’re in a drought now, with serious rain and snow deficits. And the number of people who depend on the Colorado River is closer to 40 million. But the comment about century-old water allocations being based on an unusually wet period in the river’s history? That’s exactly right — and a reality with which Western cities and farmers are still having trouble coming to grips.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.